COP16 and Peasants: the Great Transformation of the 21st century

“What we call land is an element of nature inextricably interwoven with man’s institutions. To isolate it and create a market for it was perhaps the weirdest of all the undertakings of our ancestors.” [1]

Without a doubt, a gathering like COP16 holds planetary importance, particularly when considering that the dialogue on biodiversity survival is shaped by the intensification of armed conflicts at national levels, climate-related disasters, humanitarian crises, and religious and identity-based factionalism. On top of this, the rampant inequality left by the COVID-19 pandemic has weakened progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, which, according to the UN, were already falling short by 2023 [2].

In this sense, these gatherings are more than formal discussion spaces—they are pivotal scenarios that redefine the paradigm of global governance and the renewal of an ecological pact. Therefore, it is essential to highlight why the symmetrical inclusion of rural communities is of vital importance.

Along these lines we pose three key questions: (1) What was the role of peasant participation in COP16?; (2) What is the environmental significance of small-scale peasant production territories?; and (3) What could constitute the Great Transformation of the 21st century? Our aim is to demonstrate that this transformation must place peasants and nature in the heart of society.

1. Peasants in the COP-16

Firstly, let’s review: what was the outlook of peasant participation in COP16? Although peasant communities had permanent access to the blue zone (where international negotiations were taking place) and were stationed in an independent pavilion throughout the conference, their actual participation was virtually nonexistent. Recognition and inclusion in the negotiations were minimal. For instance, only the Bolivian delegation proposed adding the term “peasants” to Article 8 (J) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which ensures the participation of civil society in decision-making regarding strategic and environmental areas. Unfortunately, neither the contact groups nor the plenaries addressed the issue of peasantry. In fact, the opposite occurred.

During the dialogues, there was a proposal to remove the term “local communities,” the only expression that links peasants to Article 8(J). While it is true that the term is somewhat ambiguous and not aligned with any international instrument, its removal—without the inclusion of some term that refers to peasants, rural workers or peasantry—would have meant ethnic unilateralism in the protection of biological diversity.

Seriously, did no one think to include in the biodiversity discussion the population group most closely linked to food production from a polyculture perspective, and who also frequently resides in environmental buffer zones? The previous balance is difficult to assess and even undermines the achievement of the goals of the Global Biodiversity Framework for several reasons, which are elaborated upon below.

a. Local communities, UNDRIP and UNDROP

Unlike the term “local communities,” peasants have a recognized instrument in the multilateral framework: the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP), adopted in New York on December 17, 2018, during the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly. In this regard, a statement from the UN Working Group on Peasants and other people living in rural areas of the Special Procedures – UN suggested that at least 8 articles of the UNDROP (5, 10, 11, 13, 15, 17, 18, and 19) were directly related to the global challenges of biodiversity conservation – CBD.

Drafting Article 1, which defines who peasants and other rights-holders are under UNDROP, took nearly 15 years to reach an agreement within the United Nations. Therefore, its conceptual precision and operational usefulness in these discussions are evident. In this sense, UNDROP, along with its twin declaration for indigenous peoples – UNDRIP, constitute the hard human rights approach for rural populations globally, and as such, they should move forward together and symmetrically in these types of discussions.

The recognition of local communities through UNDRIP and UNDROP is crucial, as their land management practices are directly linked to biodiversity conservation, sustainable agriculture, and food security, with rural populations playing a key role in protecting ecosystems and mitigating the global challenges of biodiversity loss.

b. Biodiversity, agriculture and land access

According to FAO, biodiversity—including species, genetic, and ecosystem diversity that supports food and agriculture—is declining globally. The main drivers of biodiversity loss—land-use change, climate change, pollution, overexploitation of wild species, and the spread of invasive species— can be linked to unsustainable agricultural practices [3].

Therefore, the relationship between biodiversity conservation and food production is undeniable. In fact, 95% of global food production depends on soil. However, one-third of the land is moderately to highly degraded. Species are also suffering: 28% of local livestock breeds are endangered (61% have an unknown risk status), and 38% of global fish populations are overexploited, compared to 10% reported in 1974. Additionally, 420 million hectares of land were deforested between 1990 and 2020, with 90% of that deforestation between 2000 and 2018 linked to the expansion of agricultural land use (50% for crops and 38% for livestock pastures)[4]. We are destroying what we need to survive, there is a deep connection between the decline of biological diversity and land ownership.

On one hand, FAO studies show that small farmers with less than 2 hectares cultivate only around 12% of all agricultural land, while producing approximately 35% of the world’s food. On the other hand, it is worth noting that, although indigenous peoples make up only around 6% of the global population, they manage or hold land rights to about 40% of the planet’s protected areas and ecologically intact landscapes (excluding Antarctica)[5]. This is how we can conclude that indigenous, Afro-descendant, and peasant populations are the true custodians of biodiversity, but they are in danger.

c. Territory, environment and persecution of social leaders

The UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances has recognized that individuals who defend land and the environment are often victims of systematic human rights violations. In 2023, at least 196 land and environmental defenders were killed worldwide, with the majority of these deaths attributed to actors involved in mining, fishing, illegal logging, and sectors such as agribusiness and infrastructure [6] .

Furthermore, the effects of climate change and environmental degradation disproportionately impact the most vulnerable populations, turning this issue into a profound injustice, akin to other human rights violations [7] . Particularly alarming is the situation of rural women. Between 2017 and 2021, approximately 10% of the victims were women [8] . Women, especially indigenous women, face heightened vulnerability to violence linked to environmental issues, with nearly half of all female activists being murdered for defending communal land and environmental rights [9] .

2. The environmental value of peasant territories: Colombia’s Case

The connection between ethnic territories and areas of environmental conservation seems beyond doubt. However, what is the environmental value of small-scale peasant production territories? This is a piece of data that remains difficult to obtain, given the quality of the information when compared globally, as well as the disconnection between agricultural and environmental domains in most national records.

For this reason, and considering the access to reliable information in both domains, in this second part of the text, we decided to carry out an exercise for the case of Colombia. We aim to estimate the environmental dimension of peasant territories through data on small family and peasant agriculture provided by the Rural Agricultural Planning Unit (2023)[10]. The exercise does not consider ethnic territories; instead, it only crosses peasant data with inventories of environmentally strategic territories for this country.

We selected five representative types of areas to synthesize the balance in question: i) protected areas; ii) Forest Reserve Zones under Law 2; iii) páramos; iv) wetlands; and v) aquatic ecosystems. Let’s review the results in each category.

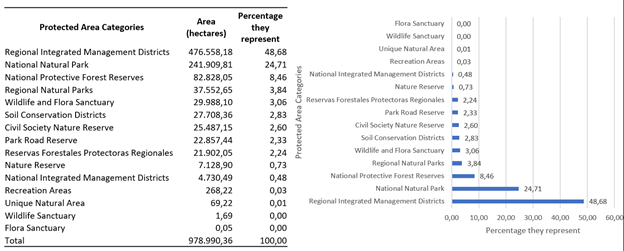

First, as seen in the graphs below, 978,990.36 hectares with probable

non-ethnic family farming overlap with protected areas, of which 48.68%

correspond to Integral Management Districts, followed by 24.71% in National

Natural Parks. Similarly, around 8.46% overlap with National Protective Forest

Reserves.

Secondly, approximately 1,633,153 hectares with probable small-scale non-ethnic family farming overlap with Forest Reserve Zones under Law 2 of 1959, of which 37% are categorized as type A zones, followed by 24% corresponding to type B zones, as shown in Table 1 below.

| Type of forest reserve area | Area (hectares) |

| Areas with Prior Zoning Decision | 309.161,35 |

| Type A | 605.589,39 |

| Type B | 388.305,99 |

| Type C | 330.097,10 |

| Total | 1.633.153,83 |

Table 1. Overlaps between Law 2 of 1959 and probable zones of non-ethnic family agriculture[11]

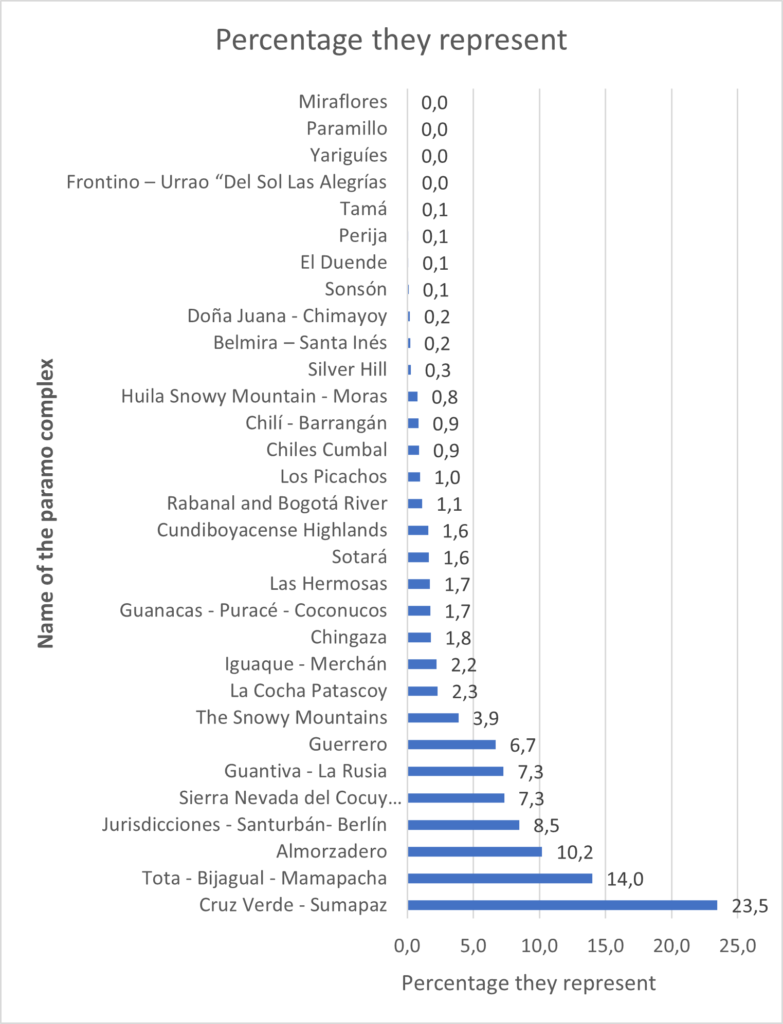

Thirdly, areas with probable non-ethnic family farming overlap with approximately 226,512.29 hectares of páramo ecosystems, of which 23.5% coincide with the Cruz Verde – Sumapaz páramo, followed by the Tota – Bijagual Mamapacha and Almorzadero páramos.

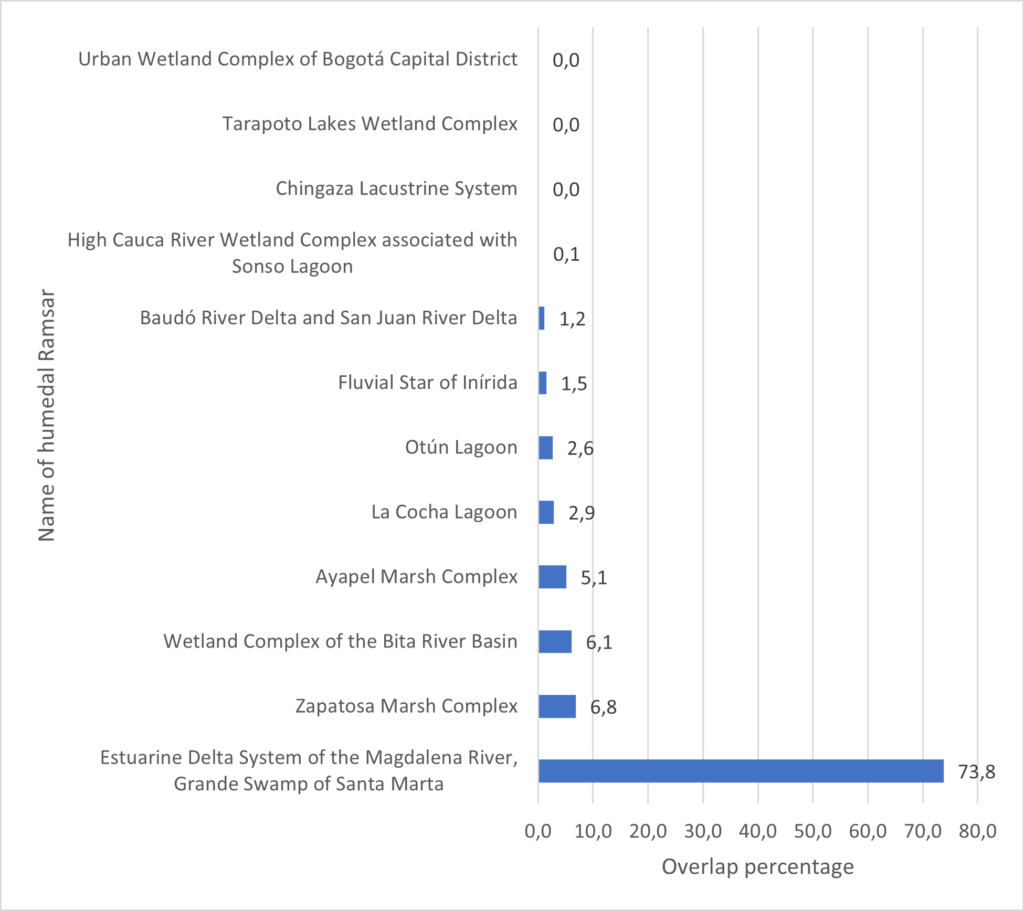

Fourthly, approximately 245,130 hectares with probable non-ethnic family farming overlap with RAMSAR Wetlands. It is worth noting that 73.8% coincide with the Estuarine Delta System of the Magdalena River, Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta.

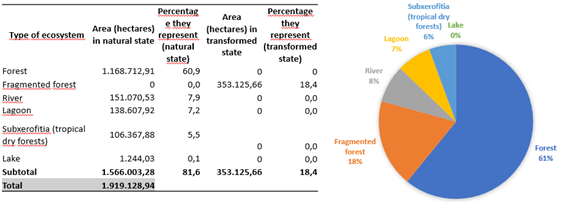

Fifthly, areas with probable non-ethnic family farming also overlap with approximately 1,919,128.94 hectares of aquatic and forest ecosystems, some of which are even linked to the national protected areas system and Forest Reserve Zones under Law 2 of 1959. Of the overlaps, 60.9% correspond to natural forests, 18.4% to fragmented forests, and 15.2% to aquatic ecosystems such as lakes, lagoons, and rivers.

By analyzing the resulting overlaps, we conclude that the relationships between rural peasant communities and nature cannot be thought of in isolation. They form a socio-ecological framework, upon which not only the buffer zones of strategically protected areas depend, but in many places, these territories are directly related to water resources (such as páramos, forests, and aquatic ecosystems).

3. The Great Transformation of the 21st Century

Finally, in this third section, we strive to affirm the importance of transforming agri-food systems twoards the conservation of global biodiversity. This, we believe, would be the great transformation of the 21st century.

According to FAO[15], agri-food systems are directly linked to more than half of the goals of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and to all the other goals in one way or another. This includes goals related to ecosystem restoration, invasive alien species, and pollution, as well as those addressing genetic resources for food and agriculture, soil health, and pollination.

In its latest study, FAO[16] quantified how transforming agri-food systems toward greater agricultural diversification could have a very positive impact on biodiversity and global food security. FAO’s preliminary calculations indicate that such transformation has the potential to increase food security for more than 1 billion people and the climate change resilience of more than 25 million people. Other biodiversity-friendly agricultural practices[17], such as agroforestry, can provide significant benefits for conservation, improving food security for those living in degraded lands, reducing soil erosion by 50%, increasing soil carbon by 21%, and boosting soil nitrogen for crops by 46%.

At COP-16, it became clear that one of the most urgent ecosystems to intervene in is the marine ecosystem. In this regard, FAO’s[18] study suggests that the recovery of overexploited marine populations could increase fish production by 16.5 million tons per year. Additionally, it would boost the contribution of marine fisheries to coastal communities and their food security, nutrition, economy, livelihoods, and well-being. Interventions in coastal and marine ecosystems could mitigate 1.4 gigatons of CO2 equivalent per year.

However, the transformation of agri-food systems faces the precarious conditions of its primary agent of change: peasants. As shown in the first report from the UN Working Group on Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, the peasantry faces multiple discriminations regarding access to land, water, public services, financial mechanisms, productive infrastructure, and justice, among others. These factors often lead to migration driven by economic or environmental reasons, forced displacements, and, as we saw earlier, systematic persecution of their individual and collective leadership.

Moreover, peasants face various discriminatory barriers in the subjective realm, which frequently leads to stigmatizations that label them as uncivilized, affiliated with armed groups, or involved in illegal mafias. This mix of objective and subjective factors highlights that the global peasantry is a highly vulnerable population that is systematically excluded from decisions that affect them, as was the case with the discussions at COP-16.

The protection of global biodiversity cannot depend on making short-term fixes to conservation paradigms. As we have observed, strengthening sustainable practices in peasant agri-food systems could help shift from a defensive conservation position in natural sanctuaries to a dynamic of transformation and progressive recovery of productive ecosystems.

In the mid-20th century, Karl Polanyi warned us that the free market would eventually break the link between labor and land. “[…] labor forms part of life; land remains a part of nature; life and nature form an articulate whole.”[19] Perhaps the Great Transformation of the 21st century lies in rethinking nature and work, not as mere commodities subject to the laws of supply and demand, but as a way to reinstate the relationship between peasants and nature at the heart of society.

[1] Karl Polanyi. 1944. The Great Transformation, p. 187.

[2] UN. 2023. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: towards a rescue plan for people and planet: report of the Secretary-General (special edition)

[3] FAO. 2024. Delivering on the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework through agrifood systems. Rome.

[4] Ibid.

[5 ] Ibid.

[6] Global Witness. 2024. Missing voices. The violent erasure of land and environmental defenders. https://www.globalwitness.org/es/missing-voices-en/

[7] Amnesty International. 2023. Climate change. https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/climate-change/

[8] Global Witness. 2021. Decade of defiance. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/decade-defiance/

[9] Ervin, J. 2018. In defense of nature: women at the forefront. PNUD. https://www.undp.org/blog/defense-nature-women-forefront

[10] Entity of the Colombian government responsible for planning and land use management in rural areas. It also plays a key role in implementing public policies related to land use, food security, land access, and environmental conservation.

[11] Source: IEI (2024), based on geoprocessing of the probable family farming layer from UPRA (2023) and the Ley 2 Forest Reserve Zones from MINAMBIENTE (2023).

[12] Source: IEI (2024), based on geoprocessing of the probable family farming layer from UPRA (2023) and the páramo ecosystem layer from MINAMBIENTE (2020).

[13] Source: IEI (2024), based on geoprocessing of the probable family farming layer from UPRA (2023) and the RAMSAR wetlands layer from MINAMBIENTE (2018).

[14] Source: IEI (2024), based on geoprocessing of the probable family farming layer from UPRA (2023), excluding overlaps with ethnic territories, and the ecosystem layer from IDEAM (2017).

[15] FAO. 2024. (Op. Cit).

[16] (Ibid).

[17] Biodiversity-friendly practices are approaches in agricultural and livestock production, forestry, fishing, and aquaculture that promote conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity (FAO 2024 Op. Cit.).

[18] (Ibid.)

[19] Karl Polanyi. 1944. The Great Transformation, p. 187.